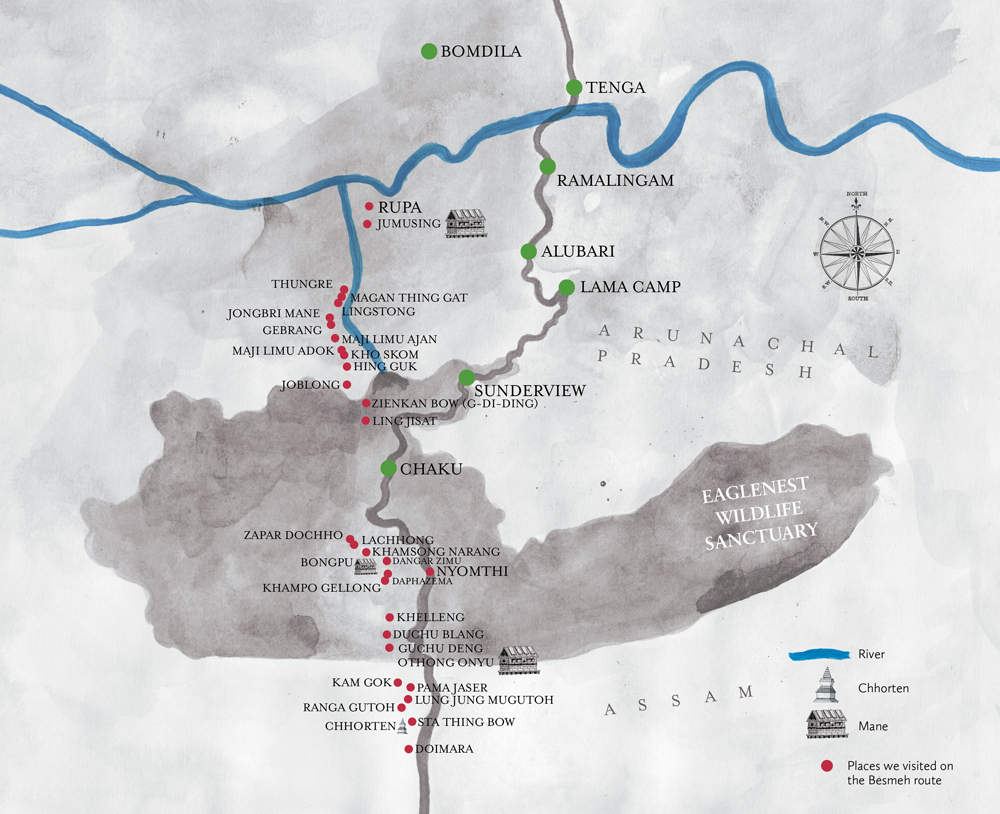

Besmeh is the tradition of the Shertukpens’ from Rupa and Thungree migrating from the mountains to the foothills of Doimara. They would spend the three months of each winter trading and bartering with the Bodos of Assam. The Rupa gompa has a preserved memory of these old connections: in 1628 AD, a mortar was presented by the Assamese king Rudro Hingho to the Shertukpen king. The relationship may have been longer and has wonderful stories of the bond between these two communities.

They started their journey in November after the Khiksabha festival.

They would halt for the first night at Octom. Groups of people would sleep around the camp-fire, which was bigger than usual to keep wild animals away. The walk the next day was much tougher. They would leave early in the morning and have packed lunch at Zienkan Bow (G-di-ding) which is close to the ridge of the highest point within Eaglenest. That night they would usually camp at Lachhong, which is the water source of Bongpu camp, now in the heart of Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary. Some would even try and walk further down to Nyomthi or Sessni. Close to the water source at Nyomthi, there were lots of wild sago palm leaves that they could feed their horses with.

On the way to Lachhong or Nyomthi there were several important places. What we know as Hornbill Point today, where you can observe a male Rufous-necked Hornbill feeding a female at a nest, also has another story of bonding. Khampo Gellong or the ‘Stone of Love’ is just below Hornbill Point. The rock still has a white-patch which used to be stacked with wild-flowers, as couples or youngsters would ask for blessings or a happy life together.

On the final day, they would make their way to the foothills. The rock at Jumu Stuh was always there and they measured their heights against it every year. There is a memorial of Tsong Poh Norpu Zangpu, a merchant who started bringing goods from Tibet to Assam three to four hundred years ago. They then finally reached Richong (or Doimara) which would be their home for the next two to three months.

At Richong, the houses and lifestyle were different from those of Rupa. For one, their houses lasted only two to three years as they were often damaged by elephants. Unlike the roofs made of dhupi wood in Rupa, in Richong they were thatched with cane and palm. Here, they would use a part of the river bank to bathe and dry themselves in the warm sunshine as the winters in Rupa were too harsh to do so.

People from all age groups would be busy on different fronts. There were teachers who would come down from Shergaon and Rupa to teach at a school in Kho-hek Bow that children from both these places would attend. The adults would go and meet the Bodos and re-kindle their old bonds. The Shertukpens would exchange maize, Sichuan peppers and other condiments that they carried and the Bodos would give them paddy, betelnut, sugarcane and things that they needed for Losar, the new year.

So what was the right time to go back to Rupa? They would ask youngsters that had made a recent trip back to Rupa or Thungree whether the oak leaves were as big as the ears of the pigs. If they were, it was also the same-time that the Large-hawk Cuckoo (Pem peyor), Indian Cuckoo (Doko plenko) and Green-backed Tit (Si-bin-bin) started to call. And group by group they would slowly but steadily filter back to Rupa and Thungree.